The Weight of Progress: Examining Obsolescence in Photographic Innovation

There's a certain melancholy that settles when you hold an antique camera. It's more than just the coolness of metal against your palm, or the satisfying click of a shutter long silenced. It's a feeling woven from the knowledge that you're cradling a relic of a different era, an era where progress marched with a steadier, more deliberate pace, and where the tools of creation were valued for their inherent craftsmanship and the human touch infused within them. We often celebrate innovation, and rightfully so, but what about the objects left behind? What is it about these obsolete camera models that speaks to us, and why do they retain such a potent allure?

Consider the Kodak Brownie, introduced in 1900. Suddenly, photography wasn's the domain of the wealthy or technically skilled. It was accessible. It democratized memory-making. The simple box camera, with its fixed focus lens and straightforward operation, allowed ordinary people to capture moments – picnics, family gatherings, holidays – and preserve them for posterity. A relative recently showed me a box of Brownie prints unearthed from their attic. Faded, brittle, and tinged with sepia, they weren't technically 'good' photographs by modern standards, but the raw authenticity of those images, the glimpse into a life lived over a century ago, was deeply moving. It underscored that the camera itself was less important than the human connection it facilitated.

The Craftsmanship of a Bygone Era

Today's digital cameras are marvels of engineering, boasting incredible resolution, sophisticated algorithms, and instant image sharing capabilities. But there's something lost in that efficiency. Antique cameras were built to last. The metal bodies were often made of brass or aluminum, meticulously machined and beautifully finished. Lenses were carefully ground and polished, exhibiting a quality of optical precision that’s increasingly rare in mass-produced consumer goods. The sheer physicality of these cameras – the heft, the feel of the leatherette, the smooth operation of the focusing mechanism – speaks to a level of care and attention to detail that’s absent in many contemporary designs.

I remember an elderly camera repairman, Mr. Henderson, who ran a small shop near my childhood home. He was a master craftsman, able to diagnose and repair virtually any antique camera that came his way. He’s gone now, but I can still recall the scent of oil and leather that permeated his workshop, and the quiet intensity with which he tackled each repair. He would explain, with a patient generosity, how a particular shutter worked, the intricacies of a lens’s construction, and the importance of preserving the original finish. He treated each camera not as a mere object, but as a piece of history, a testament to the ingenuity of its creators.

The Rise of the Rangefinder and the Demise of the Folded Lens

The early 20th century saw a flurry of innovation in camera design. Folded lens cameras, like the Kodak Master and the ICA, were incredibly popular, offering a compact form factor and surprisingly good image quality. However, they suffered from a characteristic "parallax error" – a discrepancy between what the viewfinder showed and what the lens would actually capture. This was particularly problematic for composition, especially when photographing closer subjects. The simultaneous rise of the rangefinder camera, with its built-in focusing system and accurate viewfinder alignment, signaled the beginning of the folded lens camera's decline.

While technically superior, the rangefinder's ascendancy wasn’s solely about performance. It marked a shift in photographic priorities. The folded lens camera, with its simplicity and tactile charm, was gradually replaced by more complex, feature-rich models designed for a more technically inclined user. The aesthetic, too, changed. The elegant curves and ornate detailing of the folded lens camera gave way to a more utilitarian, industrial design.

The Shutter's Song: Preservation and Appreciation

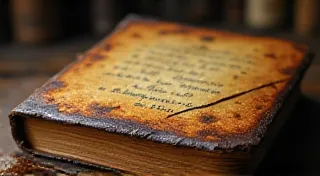

Collecting antique cameras isn't just about acquiring objects. It’s about connecting with the past, understanding the evolution of technology, and appreciating the artistry of the craftsmen who built these remarkable machines. Restoration, when approached thoughtfully, can be a rewarding process. However, it’s crucial to prioritize preservation over aggressive renovation. Stripping away the original finish, replacing period-correct parts with modern substitutes, or altering the camera’s functionality diminishes its historical significance.

There's a profound satisfaction in making a long-dormant shutter click again, in seeing a bellows expand and contract, and in knowing that you’ve played a small part in keeping a piece of photographic history alive. Even if the camera doesn’t function perfectly, its presence in a collection, its display in a well-lit cabinet, serves as a silent testament to a bygone era, a reminder of the ingenuity and dedication that shaped the world of photography. The value isn’t solely in its monetary worth; it lies in its story, its legacy, and the memories it evokes.

Beyond the Lens: The Emotional Weight

The obsolescence of these cameras isn't a tragedy, but a natural consequence of progress. Yet, it carries an emotional resonance. Holding a forgotten tool of creativity prompts reflection. It's a tangible link to generations who found joy in the simple act of capturing a moment. Their images, often imperfect by modern standards, possess a sincerity and authenticity that's increasingly rare in our hyper-edited digital world.

My grandfather, a quiet and unassuming man, left behind a collection of cameras – a mixture of box cameras, folding cameras, and a couple of more sophisticated models. They weren't particularly valuable, but they offered a profound insight into his life, his interests, and his connection to the world. They were more than just cameras; they were conduits to his memory, fragments of his history. And that, I realize, is the true weight of progress – not just the advancement of technology, but the quiet loss of the objects that once shaped our lives, and the poignant beauty that remains in their preservation.