Chromatic Whispers: How Early Film Stock Defined an Era's Aesthetic

The click of a shutter isn't just a mechanical sound; it’s the echo of a moment frozen in time. But what if that moment wasn’t captured in pristine clarity, as we expect today? What if the very materials that recorded that memory – the early film stocks – possessed inherent limitations, quirks, and imperfections that profoundly shaped the visual language of photography for decades? That's the story of chromatic whispers - the subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, influence of early film upon the art of capturing the world.

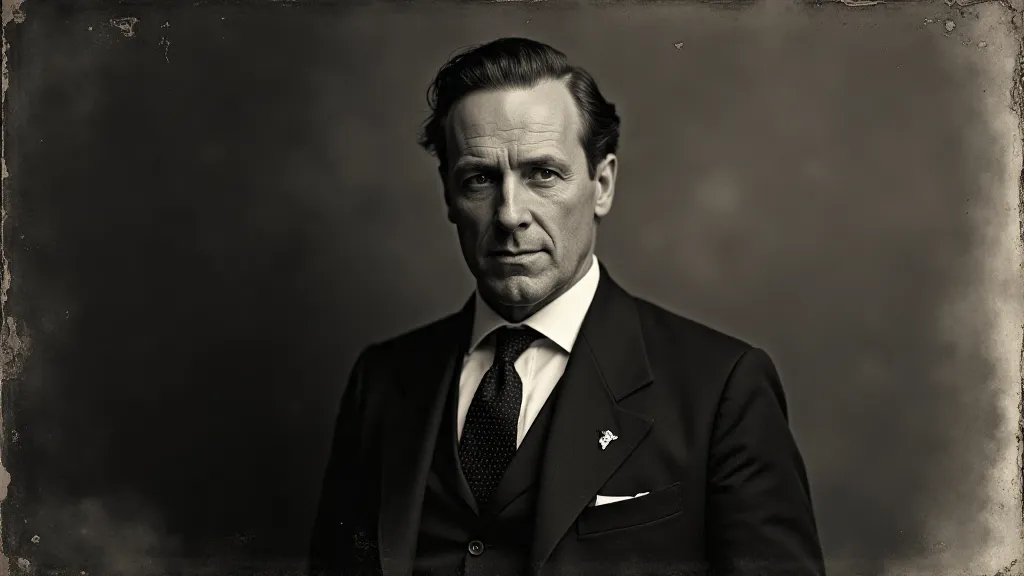

For the modern eye, accustomed to the high dynamic range and vibrant colors of digital photography, the images produced by early photographic processes – the daguerreotypes, the calotypes, the wet plate collodion – can seem strangely muted, even melancholic. It’s easy to dismiss them as simply “old” or “primitive.” But to truly appreciate them, we must understand the science – and the constraints – of their creation. These weren’t mere technical shortcomings; they were ingredients in a unique and beautiful aesthetic.

The Science of Subtlety: Early Film Stock Composition

Early photographic film wasn't the consistent, predictable medium we know today. The very composition of these materials dictated the aesthetic outcomes. Daguerreotypes, while incredibly detailed, were essentially polished silver plates treated with iodine and mercury vapor. Calotypes, pioneered by William Henry Fox Talbot, used paper coated with silver iodide. But perhaps the most influential and pervasive early film was the wet plate collodion process.

Developed in the 1850s, the wet plate collodion process involved coating a glass or metal plate with collodion (a sticky, transparent substance) and then sensitizing it with silver nitrate. The crucial – and incredibly inconvenient – aspect was that the plate had to be exposed while still wet. This imposed a strict timeline, demanding photographers be both technically skilled and incredibly swift. The resulting negatives were notoriously fragile and difficult to produce, contributing significantly to the laborious nature of early photography.

Beyond the technical challenges, the chemical composition itself imparted a distinctive visual character. Early film lacked the vibrant color range we now take for granted. The sensitivity to different wavelengths of light was limited, resulting in a tendency towards muted tones – browns, sepia, and soft greys. The spectral sensitivity was uneven; blues and greens were often rendered inaccurately, while reds and oranges tended to be lost or transformed. This wasn’t a failure of the technology; it was a fundamental characteristic of the materials used.

The 'Accidental Beauty' of Limitations

The limitations of early film stock didn't stifle creativity; they fostered it. Photographers adapted, learned to compensate, and, in doing so, inadvertently shaped the aesthetic of the era. The tendency towards muted tones became a hallmark of the Victorian aesthetic, lending a sense of dignity, solemnity, and romanticism to portraits and landscapes. The tendency for reds to disappear gave images a ghostly, ethereal quality, perfect for capturing scenes of loss or nostalgia.

Think of the countless portraits from the mid-19th century. The stiff poses, the formal attire, the subdued lighting - these weren't merely conventions of the time; they were strategies for dealing with the limitations of the medium. Brightly colored fabrics would often appear dull or distorted, leading photographers to favor darker, more muted tones. Similarly, strong sunlight was often avoided, as it could easily overexpose the film and wash out details.

Consider the landscapes. The lack of vibrant greens and blues in early film often lent a dreamlike quality to scenes of nature, softening the harsh realities of the world and evoking a sense of idealized beauty. Mountains appeared majestic but shrouded in mist, forests were rendered in shades of grey and brown, and rivers flowed like ribbons of silver. It was a romanticized view of nature, filtered through the lens of imperfect technology.

Kodak’s Revolution and the Gradual Shift

The introduction of roll film by George Eastman and the Kodak company in 1889 marked a significant turning point. For the first time, photography became accessible to the masses. While early Kodak films still had limitations – they were still relatively insensitive compared to modern film – the convenience and ease of use democratized the medium and ushered in a new era of photographic expression.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, film technology continued to evolve. Panchromatic film, which was sensitive to all colors of light, began to replace orthochromatic film (which was less sensitive to red light), gradually expanding the color range and improving the accuracy of image reproduction. The introduction of color film in the early 20th century, while initially expensive and complex, further revolutionized the medium and brought the dream of capturing the world in its full glory closer to reality.

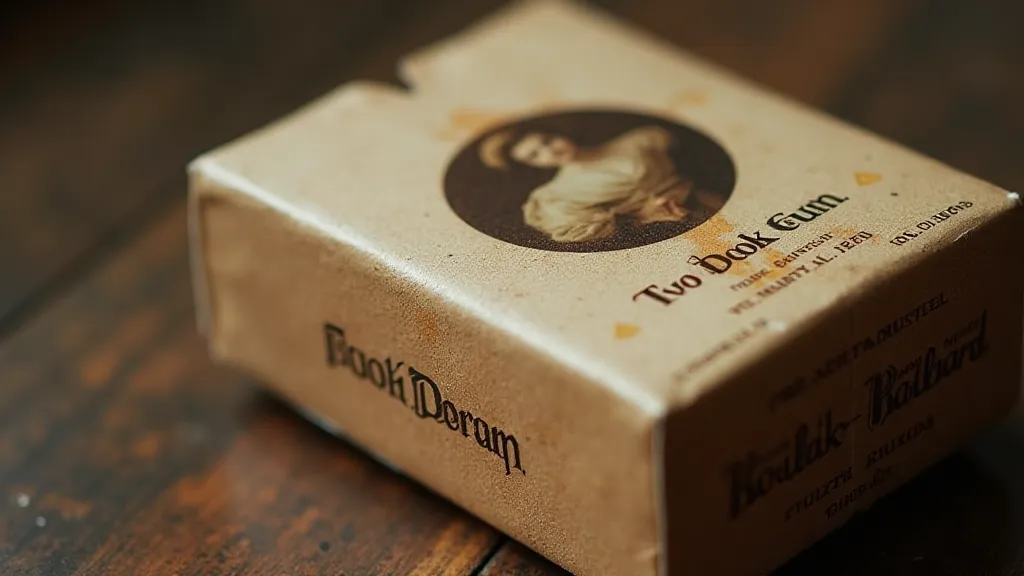

Collecting & Appreciating the Chromatic Whispers

For collectors of antique cameras and photographs, appreciating the “chromatic whispers” of early film requires a different mindset. It's not about lamenting the limitations of the technology; it's about understanding how those limitations shaped the aesthetic of an era. It’s about recognizing the artistry and ingenuity of the photographers who worked within those constraints.

Restoration of early photographs is a delicate process. Attempting to “correct” the color imbalances or eliminate the grain can often strip away the character and authenticity of the image. The goal should be to stabilize the photograph and preserve its existing qualities, allowing future generations to experience the beauty and history it represents.

When examining antique photographs, pay attention to the subtle nuances of tone and color. Notice how the absence of certain colors creates a unique visual effect. Consider the context in which the photograph was taken and the challenges the photographer faced. By doing so, you can begin to appreciate the true artistry and historical significance of these remarkable artifacts.

The chromatic whispers of early film stock are a testament to the enduring power of creativity and adaptation. They remind us that limitations can be a catalyst for innovation, and that even the most imperfect technology can produce works of extraordinary beauty.