The Ghost in the Brass: Exploring Absence in Pre-War Photographic Portraits

There’s a stillness in pre-war photographic portraits that transcends the mere absence of motion. It’s a stillness imbued with a particular kind of melancholy, a sense of irrevocable distance. We look at these images – sepia-toned, formally posed, utterly devoid of the immediacy of color – and we see not just individuals frozen in time, but echoes of a world slipping away, a world where photography itself was a ritual, a solemn occasion, rather than the instantaneous capture it is today. It’s a feeling I first understood holding my grandfather’s Kodak Brownie box camera; its heavy, simple form hinting at an era of deliberate action and enduring quality.

The Ritual of Representation

Consider the context. Before the advent of affordable color photography, these portraits were often the *only* visual record a family possessed of a loved one. The subject, typically dressed in their finest attire, likely sat for the photographer in a carefully arranged studio setting. Poses were standardized, dictated by convention and the perceived notions of respectability. Spontaneity was eschewed in favor of a carefully crafted image, intended to represent the subject's best self to future generations. This inherent formality, while perhaps appearing stiff to modern eyes, was a sign of reverence. It was a deliberate act of preservation, a conscious effort to defy the inevitable march of time.

My own collection began with a single photograph, discovered tucked away in a forgotten trunk: a young woman in a high-necked dress, her gaze fixed on a point beyond the lens. There was a quiet strength in her expression, a resilience that felt both familiar and profoundly distant. I began to seek out others, drawn to the stories they seemed to hold, the silent narratives whispered through the silver nitrate.

The Absence of Color: A Palette of Emotion

The lack of color isn't merely a technical limitation; it's an integral part of the emotional landscape. The monochromatic palette – the range of grays and browns – lends itself to a particular kind of introspection. It removes the distractions of vibrant hues, forcing us to focus on the details of the subject's face, their clothing, the subtle nuances of their posture. The absence of color also creates a sense of timelessness, transporting us to a world seemingly untouched by the relentless passage of time. It evokes a sense of nostalgia, a yearning for a past that can never be fully recovered.

The process of converting a color photograph to monochrome, even with modern digital tools, rarely captures the same quality as an original black and white print. There’s a certain depth, a richness, that is inherent in the older photographic processes – the wet collodion, the albumen prints, the platinum-palladium – that is difficult to replicate. These techniques weren’s simply methods of recording light; they were artistic endeavors, demanding precision and skill.

The Cameras Themselves: Instruments of Memory

The cameras used to create these portraits—Kodar Brownies, Folx Cameras, Premo Cameras—were more than just mechanical devices. They were instruments of memory, meticulously crafted from brass, wood, and leather. The weight of a Kodak Brownie, the feel of its bellows, the click of its shutter – these are tactile experiences that connect us to the photographers who came before us. They were tools that demanded respect, requiring careful handling and a deep understanding of the photographic process.

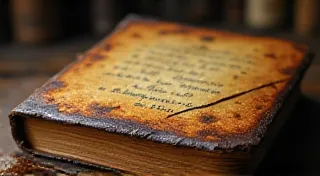

I once acquired a battered Premo camera, its leatherette covering peeling and its brass tarnished. Holding it, I felt a strange connection to its previous owner – a family photographer, perhaps, capturing moments of joy and sorrow for generations of his community. The camera wasn’t merely a tool; it was a repository of memories, a silent witness to the unfolding drama of human life.

Restoration and Appreciation: Preserving the Echoes

The restoration of antique cameras is a delicate art. It’s not simply about cleaning and repairing; it's about preserving the integrity of the object, respecting its history. Replacing original parts can compromise the camera's value and character. The goal is to stabilize the camera, allowing it to function reliably, while retaining its authentic patina. This same philosophy applies to preserving the photographs themselves; improper storage or handling can cause irreversible damage.

Collecting these cameras isn't about acquiring a trophy collection of pristine objects. It's about engaging with the history of photography, understanding the evolution of technology, and appreciating the artistry involved in creating these enduring images. It's about connecting with the people who came before us, the photographers who captured moments of joy and sorrow, the subjects who posed for the lens, and the families who treasured these photographs as precious heirlooms.

The Subtle Impact: More Than Meets the Eye

The power of these portraits lies not just in their historical significance, but in their ability to evoke a profound emotional response. The formal poses, the lack of color, the inherent stillness – these elements combine to create a sense of melancholic detachment, a feeling of irrevocable distance. We see not just individuals frozen in time, but echoes of a world slipping away, a world where photography itself was a ritual, a solemn occasion. It’s a reminder of our own mortality, a poignant reflection on the fleeting nature of time.

In a world saturated with digital images, the deliberate slowness and tangible presence of these pre-war portraits offer a much-needed respite. They invite us to slow down, to contemplate, to connect with a past that, despite its distance, remains remarkably relevant. They are, in essence, more than just photographs; they are windows into the souls of those who came before us, echoes of a world that deserves to be remembered.